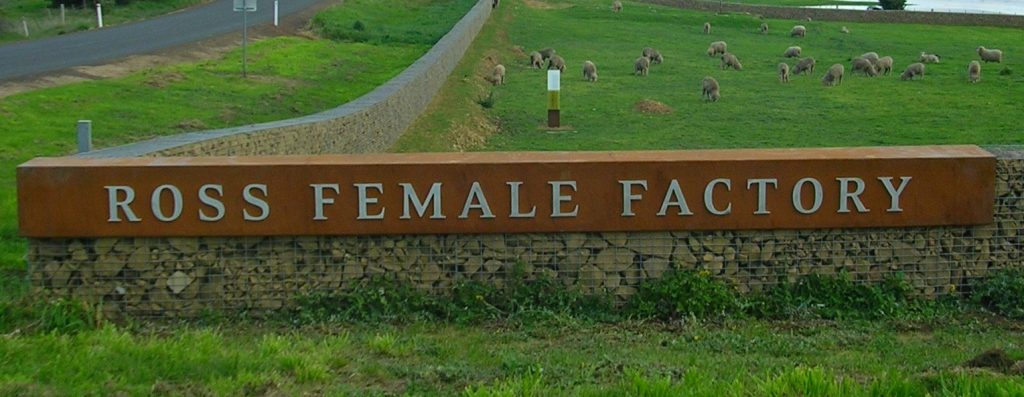

Female Factory

Location: Portugal Street, Ross. Open daily 10am – 3pm.

What images do the words Female Factory conjure up for you? Female Factories were actually women’s prisons. They were places of punishment with the job of teaching women ‘habits of Industry’ so that they became useful to society rather than burdens upon it.*

The Ross Female Factory was one of 5 in Tasmania. It has been the site of three excavations which uncovered intriguing stories. Today, the quiet, undulating paddock is peaceful and you can see interpretation around the site. In the Commandants Cottage there is a scale model of the site, and further stories of the women who came through here, and how their lives unfolded.

Interested in knowing more?

Built in the early 1840s, this probation station incarcerated female convicts from 1847 to 1854, when the Transportation System ceased operation. The Ross Factory was one of four networked women’s prisons that operated during Tasmania’s convict era. Today, the Ross Female Factory is a protected Historic Site, managed by the Parks and Wildlife Service and the Tasmanian Wool Centre of Ross.

Open to the public, the Overseer’s Cottage contains a display on the history of this unique convict site, including a model of the Female Factory in 1851.

Ross Female Factory Archaeological Survey

Background

Britain began transporting convicts to New South Wales in 1788. After the establishment of Van Diemen’s Land in 1803, Britain began transporting convicts to this island colony. Over 12,000 women came to Tasmania over the 50 year Convict Era. Women were typically sentenced for periods of 7 or 14 years, usually for petty theft from their employers in England. In the penal colony, women were either assigned as domestic servants to free settlers or were incarcerated within the Female Factories. This name was abbreviated from the British institutional title “Manufactory” and referred to the prisons’ role as a Work House. While incarcerated within a Female Factory, the inmates worked at laundry and sewing brought in on contract from the local community. Convicts were divided into three classes:

The Punishment Class: sentenced to periods of “separate confinement” in the Solitary Cells.

The Crime Class: incarcerated within the prison.

The Hiring Class: given privileged positions within the Factory until they were assigned as domestic servants to local properties.

The Ross Female Factory also housed the babies of convict women in a Nursery Ward. An enforced early weaning age and unhygienic conditions resulted in very high infant mortality rates within the factories.

Excavations

Preliminary results of the archaeological excavations have provided some new images of daily life experiences for female convicts at the Ross site. Summer field seasons in 1995 and 1997 opened 105 square meters, excavating three areas within the Ross Female Factory: the Crime Class, the demoted Solitary Cells, and the promoted Hiring Class. These three areas represented the three stages of reform that female convicts passed through during their incarceration. A small portion of the Assistant Superintendent’s Quarters was also excavated. Artifacts and architectural remains discovered through the archaeological excavation are being used to compare daily life within different parts of this prison.

Information on the excavation can be found in the Tasmanian Wool Centre history museum.

Area C: The Solitary Cells

The Ross Factory Solitary Cells are highly significant as the only remaining separate treatment cells built explicitly for punishment of female convicts. Architecturally, the Solitary Cells were designed to maximise the isolation of inmates. Rough cut sandstone walls, approximately 50cm thick, contained women undergoing “separate treatment”, minimizing sound transfer and communication between cells. Archaeological excavations determined individual cells were approximately 1.3 metres wide by 2 meters long, or roughly 4 by 6 feet, a space just large enough to accommodate a single inmate.

Period architectural plans suggest the cells were entered from the northern exterior. Archaeological evidence for the location of cell doors remains ambiguous, with post-Factory period recycling and demolition removing most of the structure including all door sills or stairways which might have existed.

Unlike structures in the main Factory compound, the Solitary Cells contained packed earthen floors. Furthermore, these floors appear to be significantly lower than the cell doors. Floor features underlay 35cm to 50cm of demolition debris and structural collapse. This evidence suggests that entry into a Solitary Cell required a descent of more than half a metre, suggesting interior stairs once existed for each cell.

Regardless of the height of the original doors, to undergo “separate treatment,” convict women descended into a cramped, darkened, silent cell for up to three weeks of isolation. This spatial movement can be interpreted as a metaphor of punishment and atonement, with the stigmatized woman descending into her solitary cell, reforming through silent prayer and contemplation, and ascending upwards to rejoin the general penal community once her sentenced period of separate treatment had been served.

Archaeological deposits within the Ross Factory Solitary Cells reflect constant power struggles between Factory inmates and guards.

Experiencing the degradation and isolation of architecturally enforced “separate treatment”, female convicts appear to have minimized their disadvantage through importation of forbidden luxuries – archaeological evidence of tobacco, alcohol and increased food rations were recovered in each excavated cell. At some point after 1851, a fire occurred within the Solitary Cells, concentrated in the southern half of one cell, but affecting at least the two adjoining cells. Since documents from other Female Factories suggest female convicts committed arson to create public spectacles of violent confrontation, the burning of the Ross Solitary Cells could be interpreted as a similar event. Provoked by such brazen disobedience, and saddled with a semi-functional cellblock, Ross Factory authorities responded by restoring the structure. The Solitary Cells were relayed with a second floor layer of hard clayey-silt. These new earthen floors were less easily adapted, and more easily inspected, for caches of forbidden materials.

However, power struggles continued. The new floors, probably accompanied by tightened penal regulations, were partially successful disciplinary tactics, and the frequency of these “luxuries” appearing in the Solitary Cells decreased. However, the trade did continue, and archaeological evidence accumulated within the second floor feature. The material residues of these insubordinate activities were both scattered through the new floor, and concentrated inside a small pit dug within the western cell.

Source: Parks & Wildlife Tasmania

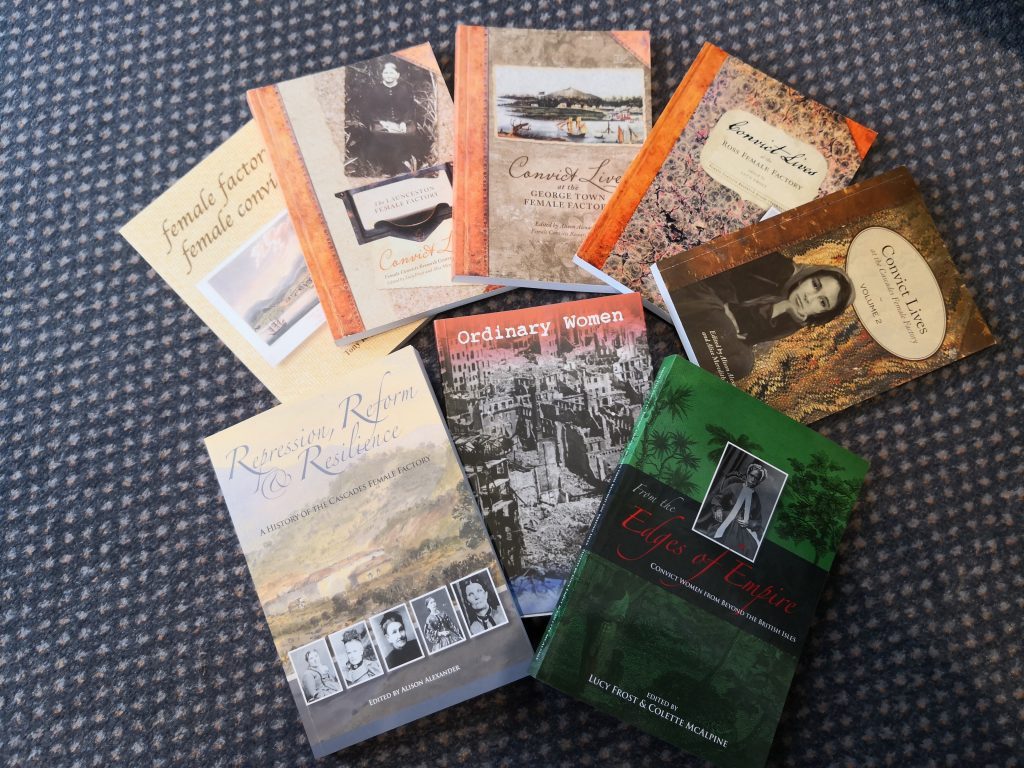

Further reading

There are books available at the Tasmanian Wool Centre telling the stories of the Female Factories and convict women.

Excellent further reading is here, an in depth report by Eleanor Casella including very good images of excavations.

*https://www.utas.edu.au/library/companion_to_tasmanian_history/F/Female%20factories.htm